The Illinois-based health care company Baxter was an early adopter of Halo’s R&D partnering platform and has executed five RFPs to date.

On a recent episode of the Inside Outside Innovation podcast, host Brian Ardinger invited Kevin Leland, CEO and Founder of Halo, and Matt Muller, Director of Applied Innovation at Baxter, to give listeners a sneak peek into Baxter’s dialysis research and the novel connections his team uncovered through engaging in Halo’s network. (Read a case study of the partnership.)

You can listen to the episode here and follow along with the transcript below.

Brian Ardinger: Welcome to another episode of Inside Outside Innovation. I’m your host, Brian Ardinger. And as always, we have another amazing set of guests. Today, we have Kevin Leland, who is the CEO and Founder of Halo. And Matt Muller, who is the Director of Applied Innovation at Baxter. Welcome.

Kevin Leland: Thank you.

Brian Ardinger: Hey, I’m excited to have you both on the show to talk about a topic that’s near and dear to a lot of folks out there. That’s the topic of open innovation and how corporations and startups and new ideas get started in this whole world of collaborative innovation. Kevin, you’re the CEO and founder of Halo. What is Halo? And how did you get started in this open innovation space?

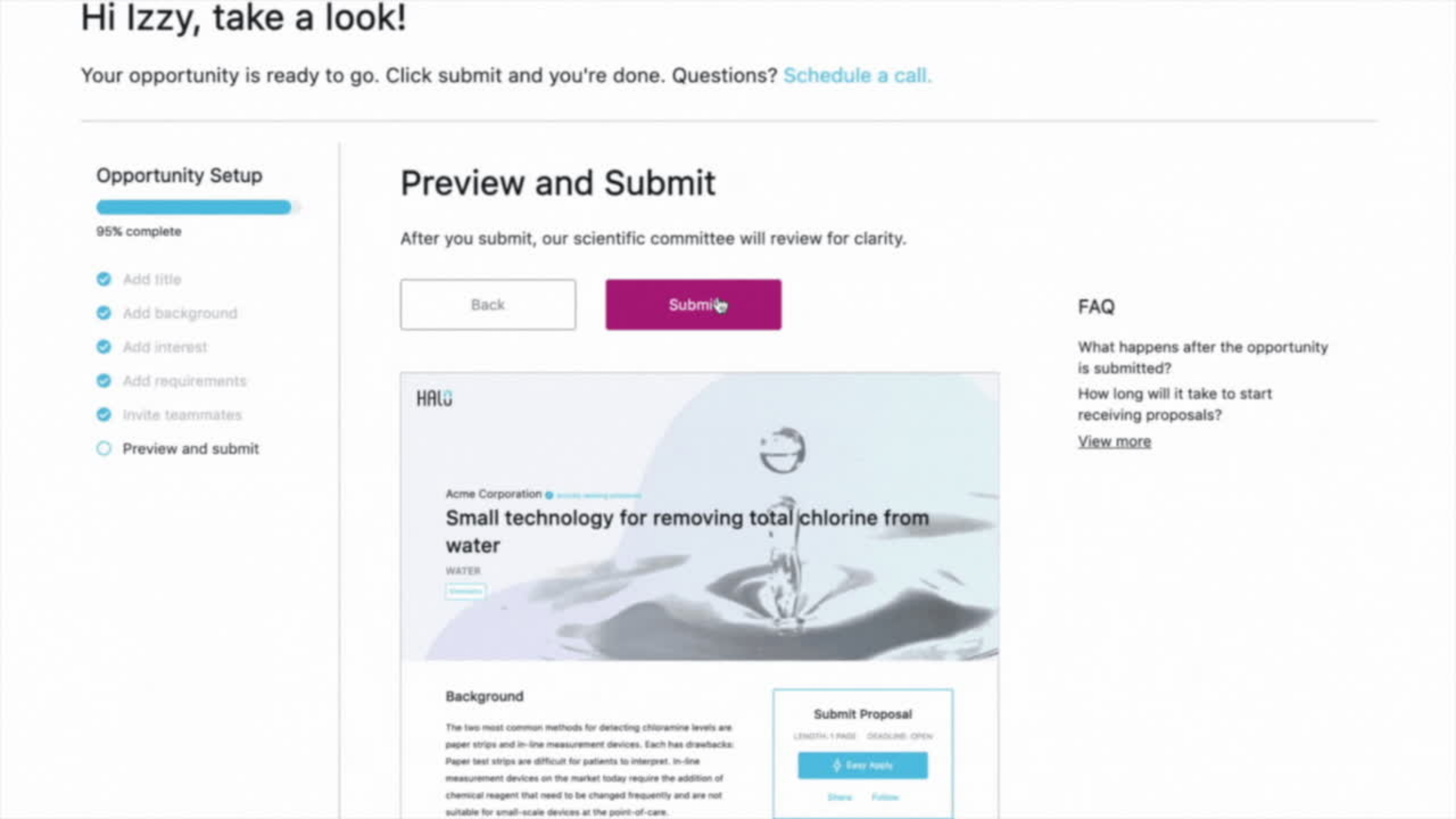

Kevin Leland: Halo is a marketplace and network where companies connect directly with scientists and startups for research collaborations. It’s about as simple to post an RFP or a partnering opportunity on Halo as it is to post a job on LinkedIn. And then once it’s posted, scientists submit their research proposals. We went live in January. Matt and the team at Baxter were our very first customers. So, they were the earliest of early adopters and a really fantastic partner.

I came across the idea of Halo and got into open innovation really kind of by accident. The original concept for Halo was crowdfunding for medical research. So, a little bit different, but we would work with technology transfer offices at universities to identify promising technology that just needed a little bit of funding to get to the next level.

And through that experience, I learned that scientists needed more than just funding. They needed the expertise and the resources of industry. Meanwhile, I was learning how industry was actively trying to partner with these scientists and these early-stage startups, because they realized that they were less good at the early-stage discovery process of research. To me, it seemed like an obvious marketplace solution. That’s where the impetus of the business came and how we started.

Brian Ardinger: Let’s turn it over to you, Matt. From the other side of the table, from a corporation, trying to understand and facilitate and accelerate innovation efforts. What does open innovation mean to you, and how did Halo come to play a part in that?

Matt Muller: As you mentioned earlier, I’m Director of Applied Innovation here at Baxter and I am in our Renal Care Business. That’s the business at Baxter that’s focused on treating end-stage kidney disease, one of Baxter’s largest businesses. As a company, we have over $12 billion in sales annually, and dialysis in the renal care business is our largest business unit.

It is an area that we’ve struggled with innovation. At Baxter, we particularly excel at treating kidney disease in the home. This is a particular therapy called peritoneal dialysis, where patients are able to do it in their home while they sleep.

One of the big challenges that we have today with peritoneal dialysis is that patients need dialysis solution. They use about 12, 15 liters of this sterile medical solution every night to do their therapy. Today the way we do that and the way we’ve done it ever since this therapy has been around since the early seventies is we literally deliver that solution in bags, by trucks. We make it in big plants in the United States and trucks drive all across the country and they deliver it to patients in their home.

As a company, we have said for a long time that we really need to change this business model. It’s not sustainable for us. It requires our patients to store a lot of the solution in their home. They have to essentially dedicate a whole room of their houses to storage of their supplies.

We have said for the longest time that we want to change how this is done. We want to be able to use the patient’s own water in their home. Instead of delivering all these bags of solutions, we want to deliver concentrates, much like if you buy a soft drink at the movie theater, it comes from a concentrated box of syrup that you add water to and you have your soft drink.

That’s our vision. We’ve struggled for many years on how to bring innovation into the marketplace for making that pure water that we need in the home. We have a lot of very bright scientists at Baxter. The problem is that as Kevin mentioned before, our scientists are really good at solving particular problems, in particular getting products to market.

Where we’ve been struggling is that the science has not or at least we haven’t been aware of the science that could really allow us to break this barrier and make the leap to be able to make this pure medical-grade solution in the home.

That’s why we’ve reached out to Kevin and his platform, to go out to a really broad community of researchers to bring new ideas into the company, to help us figure out new ways to approach the problem.

That’s why we’ve reached out to Kevin and his platform, to go out to a really broad community of researchers to bring new ideas into the company, to help us figure out new ways to approach the problem.

Matt Muller

Brian Ardinger: The history of open innovation is long. And there’s a lot of things that have been tried in the past. Did Baxter try other methods in the past? Or how did you go about trying to determine what things we should innovate internally and try to solve that way versus when and where we go outside for solutions?

Matt Muller: I would say as a company, we probably hadn’t been as involved specifically in the university and in the startups space. So, a lot of times as a company, we have a lot of people that come to us with ideas and looking for funding. It’s a very common proposition that they give you.

They need a certain amount of funding, and in three years, they’ll have a product. Three years is like the magic number. The reality is that frequently the claims and the maturity are very oversold, and we haven’t been really successful in that type of space. And so, we’ve been really looking at different ways to engage a larger community.

The other element of it too is sometimes when you talk about open innovation, we’re limited by our existing network of people. That includes our employees and who they work with. Maybe it’s the fact we’re in Northern Illinois, we’re close to Northwestern University, and people here have relationships with professors at Northwestern.

So, we develop those relationships and open innovation opportunities through those connections. We’ve been looking into how we can expand that, reach a broader audience, get a global connection, and be open to new ideas.

Brian Ardinger: And that’s a great segue. Kevin, you’ve also worked with companies besides Baxter. What are some of the typical mistakes or challenges that you see corporations making when trying to get started in open innovation?

Kevin Leland: First of all, getting started is kind of the big challenge, because there’s still some resistance to open innovation. Even the term open can be scary to some companies because it implies or it can be interpreted as we’re letting all of our competitors know what our strategic interests are.

And so, I’m even hesitant sometimes about using the word open. I mean, we’re really about facilitating partnerships between companies and researchers who have mutually shared interests and can work together to solve problems.

Some of the approaches in the past to me just seemed really inefficient, like traveling around the world and going to conferences and hoping you hear somebody speak or get a referral from someone or just call up the universities. Or being more likely to just work with Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, only select universities as if there couldn’t possibly be great research coming out anywhere else.

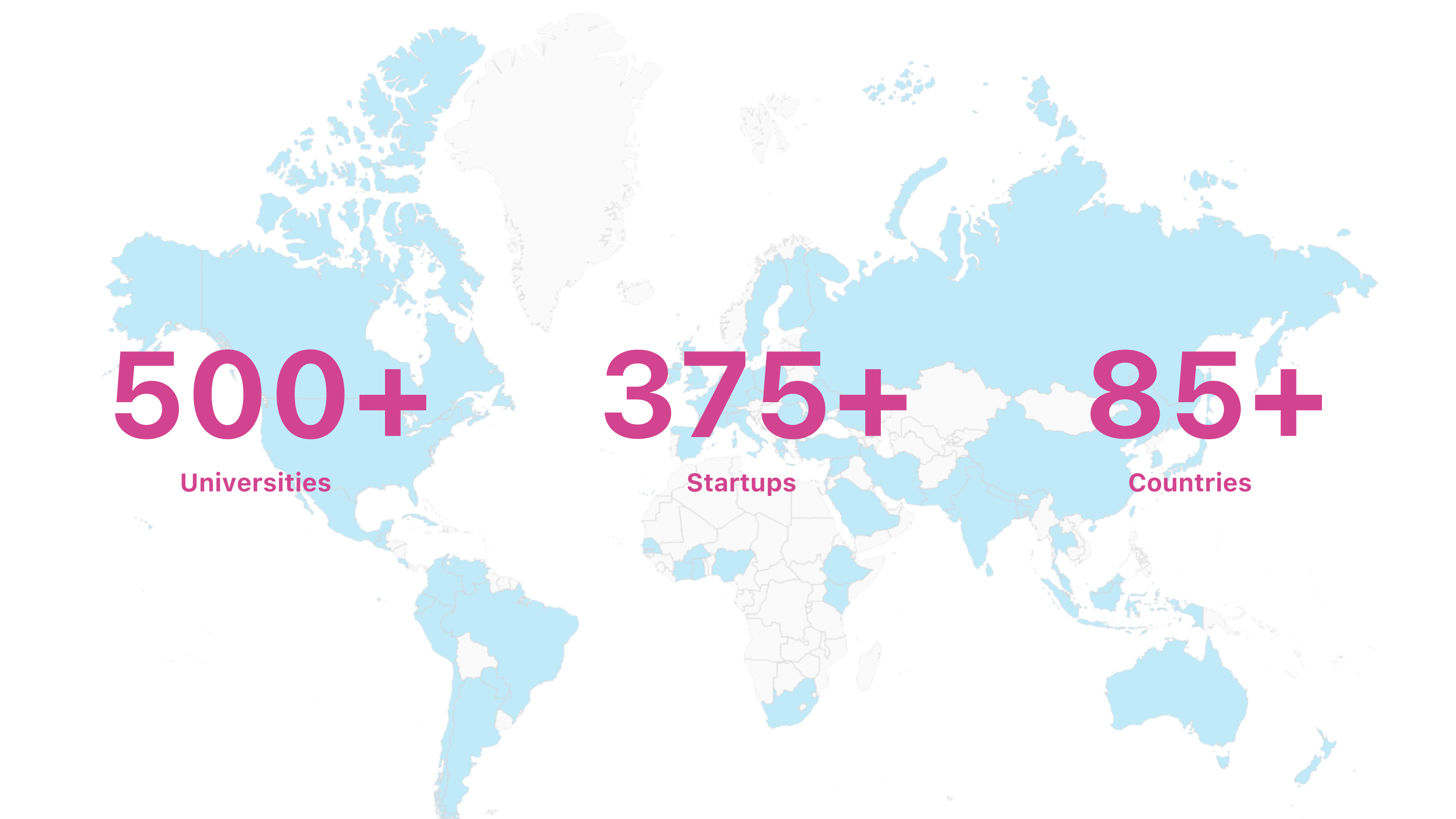

That was part of the problem that I was trying to solve with Halo in terms of democratizing access to companies like Baxter for all scientists, regardless of where they are in the world, or what institution, where they reside and making the process easier for both the scientists and for the company.

That was part of the problem that I was trying to solve with Halo in terms of democratizing access to companies like Baxter for all scientists, regardless of where they are in the world, or what institution, where they reside and making the process easier for both the scientists and for the company.

Kevin Leland

One of the reasons that companies don’t cast a wider net is because it’s tedious administrative work in terms of emailing and downloading attachments and PDFs. So, the platform is designed to streamline that entire process so they can cast a wider net.

Brian Ardinger: Are there types of businesses or types of challenges that seem to work better when tackled in this open format or open environment?

Kevin Leland: We’re focused on scientific innovation. The other key difference is that all of our community are PhDs or part of funded startups. So it’s not a challenge site where just anybody can submit an idea. That’s one of the key differences.

Brian Ardinger: Are there types of businesses or types of challenges that seem to work better in this type of environment?

Kevin Leland: In the case of Halo, we have seen everything from very specific requirements that were similar to what Baxter was looking for where they lay out the actual technical requirements of what they’re looking for. And then, on the other side of the spectrum, we have what Bayer has done, which is a very open-ended call for proposals around the area of sustainable agriculture.

And so, the platform is flexible enough that it works for either approach. It depends on the goal of the company. As in the case of Baxter, many of our other customers like Pepsi or Reckitt, they’re looking for a very specific solution to a challenge that they have. Whereas a company like Bayer doesn’t know what they don’t know, and they want to see what’s out there.

From a management perspective, when you do have a very open-ended call, you get a lot more proposals and the more specific requirements the fewer you are going to get. It depends on what your ultimate strategy is.

The other key difference is that all of our community are PhDs or part of funded startups. So it’s not a challenge site where just anybody can submit an idea.

Kevin Leland

Brian Ardinger: That’s a great way to segue it back to Matt. I’m assuming that your work with Halo is not the only type of innovation initiative that’s going on at Baxter. Can you talk a little bit about some of the other innovation efforts that are going on there, and how does your work with Halo fit in with those?

Matt Muller: As a company, much of our innovation framework is built into our core business objectives. Our company is structured in business units. As I said, I work in renal care, so we start with our business and understanding what that business strategy looks like. Where do we want to play as a company? What are the key problems that we want to solve?

I mentioned up front that one of the key problems we want to solve right now is figuring out how to be a more sustainable business and get away from shipping water across the globe. That’s a key strategic initiative for our business.

We define the key elements or the problems that we need to solve in meeting that strategic initiative. One is how do we purify water in the home? And then, we figure out what are the ways based on those specific problems we find we have, what are the best ways to solve those problems?

In some cases, we’re at a point where we need more ideas, where as a company we have stagnated and tried these pathways that are not fruitful. We keep banging our head against the wall. So, let’s really go out there and see what’s out there. And, that was an example of what we did with Halo.

We also have our own internal engineering organization. We’re a global company. There are specific things that we may do from an innovation project where we will work on it internally because we feel like we have the internal expertise. Or a lot of times what we will do is we’ll look for external partnerships and that may be through various engineering consulting companies and product development consulting companies that we may partner with because they may have very specific experiences in a space that we’re interested in or maybe an adjacent space.

That’s another big element is we get siloed and focused in medical. But there are many adjacent areas where technologies are being developed and, maybe it’s the petroleum or refining industry, or maybe it’s some other area of medical that we just don’t play in. We can bring in these consultant firms that have much broader exposure. It’s really a mix between this open concept like what we do with Halo, engineering consulting and partnerships, and then internal.

Brian Ardinger: You know the world is changing so fast and everything is happening so rapidly that it’s tough to keep up. Even if you’re an expert in your particular industry, like you said, even understanding what’s going on across industries. Kevin, can you talk a little bit about the types of industries that you serve and why a platform like this can give advantages to corporates?

Kevin Leland: Yeah, absolutely. I thought it was interesting when Matt was talking about getting inspiration from other industries like oil and gas or petroleum, because that’s really what the platform is designed for.

Researchers don’t necessarily think in terms of what the commercial application is. They think of what their expertise is. By collecting all this data on what their focus area is and then on the flip side, what companies are interested in, we can more programmatically find connections that in potential partners where otherwise they would really have no idea that there might be a fruitful opportunity there.

Researchers don’t necessarily think in terms of what the commercial application is. They think of what their expertise is. By collecting all this data on what their focus area is and then on the flip side, what companies are interested in, we can more programmatically find connections that in potential partners where otherwise they would really have no idea that there might be a fruitful opportunity there.

Kevin Leland

In general, we’ve been focused broadly on the area of sustainability, which can include anything from sustainable agriculture, like Bayer to sustainable packaging or work with PepsiCo and then water treatment, which is what we did with Matt and his team.

That’s a really broad category. We do have a few other opportunities that are kind of outside that scope. But we are also looking at doing more in the medicine and pharmaceutical areas as well.

Brian Ardinger: Matt, can you talk a little bit about the early days of finding an innovation effort like this? What were some of the challenges or pitfalls or things you had to do to get buy in and then go and actually execute on this particular challenge?

Matt Muller: It’s hard to get traction in a large company sometimes. You need a champion. Kevin has known that because we’ve actually worked together to help to get that traction within Baxter. I think it helped as we got started because Kevin had some prior connections with some core people at Baxter, which helped to get some initiative.

But I think the biggest challenge is getting started and showing the value and gaining the buy-in to get something like this funded internally in a large company. I think many people have the opinion that large companies have endless resources and can do anything they want. But the reality is everything’s looked at very closely.

You’re constantly getting distracted with the new crisis or the new area of focus, and people are constantly changing roles and companies. So, you need that champion internally. You need to then be able to get that own internal opportunity to influence, to get the approval, to fund something like this.

But then secondly, you need the success stories to come out of it, because if you don’t have that initial success, chances are that then you’re not going to get that momentum and people aren’t going to believe in following through with it. That was key to our relationship—getting initial successes that we could point to. And then, things have evolved from there.

That was key to our relationship—getting initial successes that we could point to.

Matt Muller

Brian Ardinger: And that’s a great point. I think a lot of companies are naturally more fearful because failing in an existing business model is not a good thing, but yet to innovate, you know, that there are some things that are probably not going to work. Open innovation almost gives you some opportunity to try and test and experiment a little bit outside of your core realm.

It gives you a little bit more ground cover sometimes to have different types of conversations than you would have just if it was only internal and working from that perspective. Kevin, what else are you seeing when it comes to the benefits of companies reaching outside of their four walls to create their innovation initiatives?

Kevin Leland: The biggest benefit, and maybe Matt can speak to this as well, is they are identifying partners that they would have never known about otherwise. So Matt was able to identify a team in Australia at UNSW Sydney. I don’t think Baxter has anyone on the ground there, and they probably wouldn’t have found that otherwise.

The secondary benefit is it’s almost like a market analysis tool or market intelligence tool because the companies are learning about new technologies and trends and different pockets of innovation around the world that they really didn’t have visibility into previously.

Brian Ardinger: What are you guys most excited about moving forward?

Kevin Leland: I’m really excited to see this working. I did a ton of customer discovery before launching Halo. I had dozens of interviews with innovation executives on one side and scientists on the other side. But you never really know until you actually go into the wild and introduce a platform to the users to see if it’s going to work. We have worked with twelve Fortune 500 companies. We’ve done 20 plus RFPs now since Baxter, and every one of them has resulted in signed agreements.

And, you know, obviously it takes time to see these products into the marketplace, but that’s the next thing I’m excited about is when Baxter introduces a new home dialysis device, where patients can make the dialysis solution from their kitchen and don’t have to have 900 pounds of solution sitting in their bedroom.

We have worked with twelve Fortune 500 companies. We’ve done 20+ RFPs now since Baxter, and every one of them has resulted in signed agreements.

Kevin Leland

Brian Ardinger: Matt, what are you excited about?

Matt Muller: Well, I like your vision of the future there, Kevin, first of all. Beyond that, you know, and obviously helping us accelerate getting innovative products to market, the other thing that I’ve really enjoyed is being able to make these broader connections that we never would have before. Kevin used the example of our connection with the University of New South Wales on a really interesting research project.

But the other thing that this connected us with is a whole network of experts on an NSF research center called NEWT, which is very well aligned with some of our core business and research interests that we never would have had before. You know, if we hadn’t been involved with this initiative. And so, it’s those types of things that also really get me excited because it really helps us.

You know, at the end of the day we’re scientists, we’re engineers. We all like collaborating with other scientists and engineers to solve problems. This is exciting because it broadens that network for us even more.

You know, at the end of the day we’re scientists, we’re engineers. We all like collaborating with other scientists and engineers to solve problems. This is exciting because it broadens that network for us even more.

Matt Muller

Brian Ardinger: Matt and Kevin, thank you for collaborating here at Inside Outside Innovation and sharing some of the insights on what’s working in this new changing landscape that we’re in. I appreciate you both being on. If people want to find out more about yourselves or the companies that you work at, what’s the best way to do so?

Kevin Leland: For me, they can connect with me on LinkedIn. Just search Kevin Leland. And visit our website at halo.science.

Matt Muller: And similarly, you can connect with me on LinkedIn. I’m Matthew Muller, Director of Applied Innovation, Baxter Healthcare. We also have a company bio description on Kevin’s platform, Halo. We also have put out two new challenge statements with respect to some of the key technical challenges that we have in our space. So, you know, go to Kevin’s platform and check those out as well.

Brian Ardinger: Well, Matthew, Kevin, thank you again for being on Inside Outside Innovation. I look forward to continuing the conversation and thank you very much.

Kevin Leland: Thanks, Brian.

Brian Ardinger: That’s it for another episode of Inside Outside Innovation. If you want to learn more about our team, our content, our services, check out InsideOutside.io or follow us on Twitter @theIOpodcast or @ardinger. Until next time, go out and innovate.