Q&A with Harald Steltzer, CEO of NoMo Diagnostics

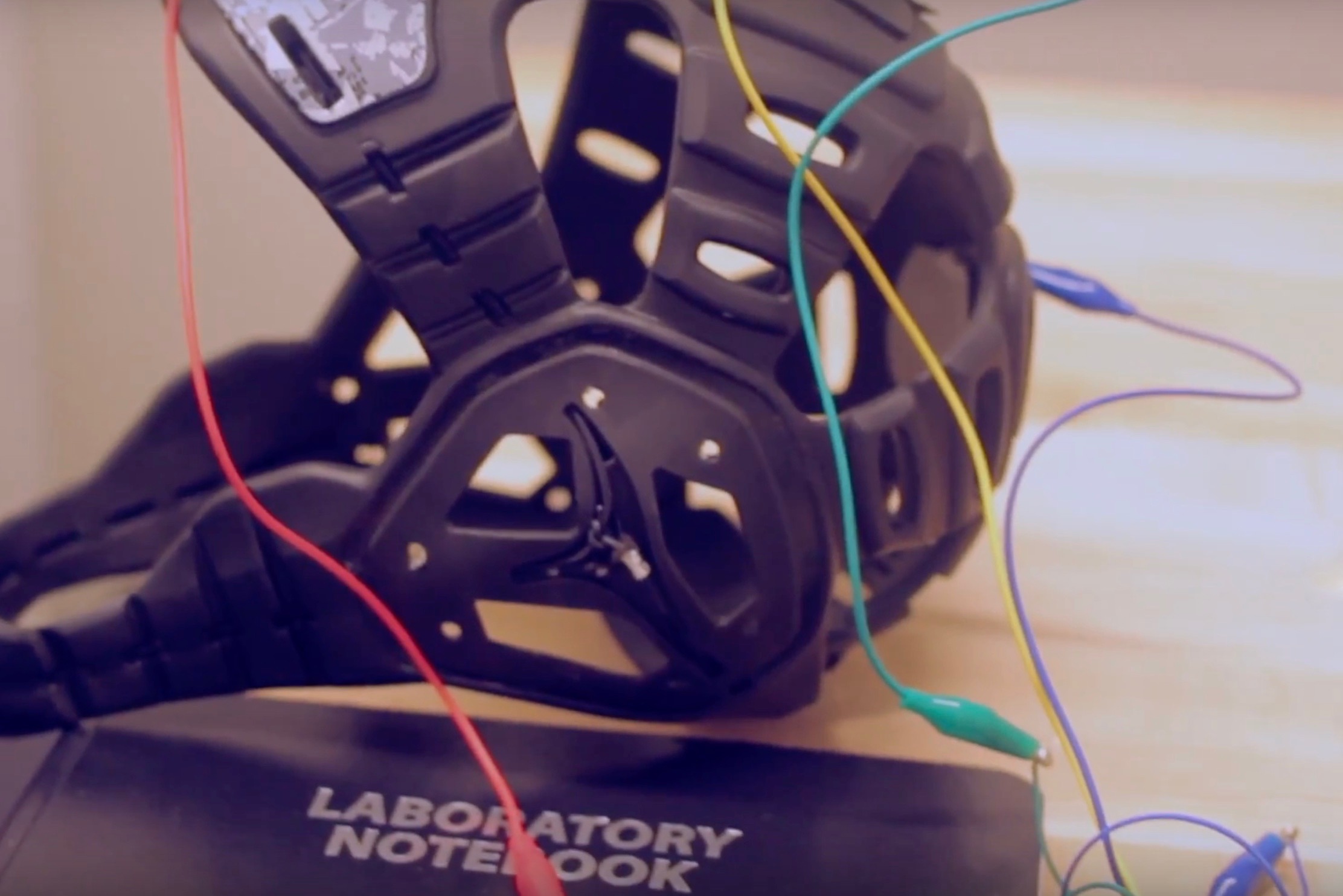

Harald Steltzer took the unusual step of canvassing university patent coffers for innovation he could spin out into a company. The fruit of his efforts is NoMo Diagnostics, a platform technology that detects concussions on-the-field in real-time and can be embedded in helmets, headgear and headbands.

Tell me about NoMo Diagnostic…

NoMo diagnostics is developing the first integrated, embedded, concussion-monitoring sensor for helmets. We leverage quantitative EEG technology and automate what a neurologist would be looking for using machine learning.

What problem is it solving?

NoMo is specifically addressing early identification of concussions – four out of every five concussions are never identified and athletes continue on and play. Soldiers continue on and fight. It’s the early warning system like a fire alarm to indicate that there’s been an injury to your brain.

It’s the early warning system like a fire alarm to indicate that there’s been an injury to your brain.

Were you actively looking for a university technology?

Yes, I purposefully went into the academic system and was actively looking for new assets and different technologies that might be ready to spin out of a university and start a company around that could leverage Chicago-area resources.

What does that process look like? How did you go about doing it?

The process for me was reaching out to venture creators and technology transfer individuals at select universities to understand what technologies they had available. They usually have a short list of five or six projects that are either ready to go or need a little extra support and mentoring.

How common is it for someone like yourself or an entrepreneur to license technology from a university as opposed to a pharma or biotech company?

It’s very unusual – I only did it because I knew how the process worked and I had contacts in the institutions. It was a very non-traditional process.

You’re not a neuroscientist and don’t have specialty in traumatic brain injury, so how were you able to evaluate this opportunity?

Years of experience in corporate development where you’re trained on how to measure up science based on market opportunity, team, patents, market size and commercial assessments. For neurodiagnostics I relied on industry experts that could help me understand what the issues may be with this sort of technology.

Had you already narrowed down your interest in neurodiagnostics or is that just where you ended up?

It’s purely where I ended up. I feel pretty comfortable that I can program manage nearly any regulated product, whether that’s a simple laboratory test or a complicated genetic disease with a biological solution.

With regard to the specific science, what I was very interested in was a great team with a white space opportunity having a large patient need. I also value sports. I’ve been an athlete. I’ve coached youth leagues and I’ve seen concussions first-hand. I wanted to figure out a way of helping preserve team contact sports for future generations so it was blending my personal interest along with my experience in life sciences.

I wanted to figure out a way of helping preserve team contact sports for future generations so it was blending my personal interest along with my experience in life sciences

Were there other opportunities that you had come across that you were considering as well?

Yes, many, many opportunities. There’s basically an unlimited pool of opportunities sitting within the universities that are just looking for a little bit more support. There’s a lot of promising assets that aren’t getting the right attention for any number of reasons – they’re either not at the right university, they haven’t been published yet in a high-level peer-reviewed journal or they’re from a first-time academic entrepreneur. It’s frustrating to know that our tax dollars are going into the NIH grants that sponsor this research, but so few of them actually become real-world solutions.

There’s basically an unlimited pool of opportunities sitting within the universities that are just looking for a little bit more support

What are some examples of the other opportunities you were considering?

I was looking at cardiac patches, oncology diagnostics, a number of rare disease products and some drugs that were being repurposed at an academic level. But I was primarily focused on academic-led initiatives rather than deprioritized assets from acquisition or pipeline realignments from big corporations.

What was your criteria to narrow down your selection?

First, the technology. How clever is the technology. How protected is it. How unique is it. What’s the competitive space around it. What’s the strategy for adding on to the intellectual property, whether it’s patentable or knowledge that you hold in-house. Also, how great a problem is it solving. Some people translate that into how big is the market opportunity, but I think they go hand-in-hand.

And then the team is critical. Having a very active and participative academic team that is going to be involved in the early science and early direction of the company is critical in getting an academic-level startup off the ground. And lastly, the timing of the opportunity. Is the market ready for the solution.

After you learned about these opportunities from the tech transfer office, what were the next steps after?

The first step with the university is understanding what they have. Once you get an early understanding of the opportunity, you typically need to go under NDA to get other, more sensitive information, particularly if you’re looking for unpublished data, patents, and that would be the next logical step. And then it’s deciding if you see a business opportunity and creating an investment thesis around what it is. How would you do it. How would you fund it. And convince yourself – this is very important – convince yourself that you’re the right person with the right plan to be able to run it through the development process and commercialization.

Convince yourself that you’re the right person with the right plan to be able to run it through the development process and commercialization.

With NoMo, what did that look like?

In terms of technology, there is nobody operating in the space. There’s no measurable intellectual property within this business. I felt that it was very unique. The market opportunity is completely untapped, and as I dug in further, I identified that there’s absolutely nobody working on a similar type of technology that’s real-time and on-the-field. Third, the team checks the boxes. They were first-time entrepreneurs, but very invested in the process and just as good pitching the opportunity as I was. As a result, with the different disciplines of engineering, clinical, neurological science and business acumen coming together, it made for a really good fit. We all just got along very well. The chemistry was wonderful.

With the different disciplines of engineering, clinical, neurological science and business acumen coming together, it made for a really good fit

What was the negotiation like with either the investigators or the tech transfer office?

There are two different levels of negotiation that goes on. One is related to ownership. Who owns what and at what level do you come in at. And so that’s the first piece. The second is negotiating with the university. It’s a combination of what stake does the university want in the company – that’s the percentage of equity – and then there’s a lot of different milestones associated with the development process. Who’s going to cover patent costs and when, then what percentage of sales. And most universities are very good at making sure that you don’t just take ownership of the patent and then resell it. They want you to do something with it, so if those conditions aren’t being met, the university has the opportunity to pull it back.

Most universities are very good at making sure that you don’t just take ownership of the patent and then resell it. They want you to do something with it

When can we start seeing NoMo technology in the United States?

We have a three-year road map. The first year is running a feasibility study. The second year is a small pilot study along with a larger pivotal trial, and then we believe we’ll have a breakthrough product designation which just allows for a more streamlined regulatory process. We’ve been estimating somewhere between three and three and half years to get the product developed and approved by the FDA.

You found the technology at Columbia University and licensed it, but you’re building the company in Chicago. Has that been a challenge having the investigators in a different location?

If the technology comes out of a local university, I’d say that there’s a lot more local support, local alumni, that are willing to help during those early days, whether that’s an angel investor or startup money of some kind. When you’re trying to bring a product into Chicago from a non-Chicago area school, the biggest challenge has been the early-stage risk capital.

If the technology comes out of a local university, I’d say that there’s a lot more local support, local alumni, that are willing to help during those early days

What advice would you give to another entrepreneur who might be interested in licensing technology from a university?

Be comfortable with the risk associated with working on one technology at one company. You need to believe passionately in the solution and the problem that you’re looking to solve, and be flexible when it inevitably takes longer to do than you think it’s going to take.

You need to believe passionately in the solution and the problem that you’re looking to solve, and be flexible when it inevitably takes longer to do than you think it’s going to take

What advice would you give to an academic scientist who might have some technology that they want to spin out, but need a business person to help grow and manage the company?

The biggest challenge for academic PIs is usually knowing how to release control and share the process with others. Too many PIs try to manage a startup the same way they manage their lab internally with an awful lot of control. That is typically a cultural issue, particularly as you’re getting a company started up because you need to share control of ownership, control of the IP, control of the strategic direction – both scientifically and commercially – and that’s a skillset some have and some don’t at the academic level.

The biggest challenge for academic PIs is usually knowing how to release control and share the process with others

How were you able to earn the trust of the Columbia scientists and make them comfortable with handing off their baby for you to lead?

You need to have those discussions upfront before you get too far down the line. If you’re not open and honest and transparent, inevitably there’s going to be a philosophical difference that you just cannot overcome.

If someone is just a really sharp person and entrepreneurial, is that sufficient to license technology out of a university, or do you really need a background in science?

You need either the experience on your own or you need to be able to have that on the team, but that experience needs to be there. Some people try to have that through advisors to the company. I’ve seen a few other ways of it being done, but it needs to be there or else the box just doesn’t get checked. There’s nobody that has a slick enough tongue that they’re able to bring in an A round without the experience there.

There’s nobody that has a slick enough tongue that they’re able to bring in an A round without the experience there.